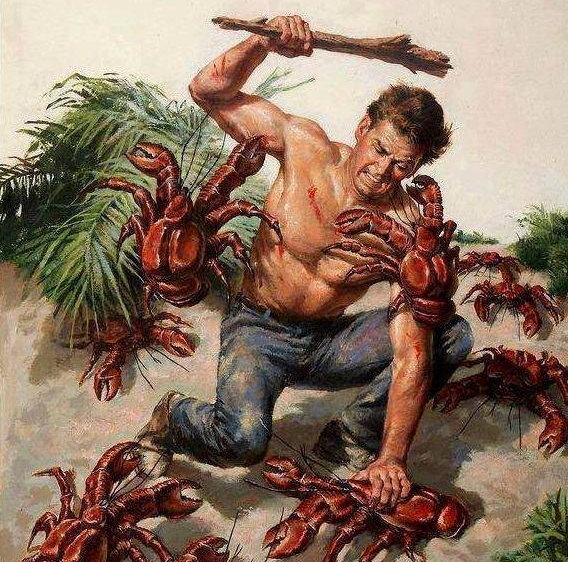

As my father overturned the seaweed-encrusted rock, a flurry of claws and chitin erupted as the crustaceous horrors lurking beneath scuttled maddeningly in all directions—their legs clacked and clambered against wet sand in a desperate struggle to hide from the sun. The event certainly changed the atmosphere of family beach day. I’d never been fond of crabs, but to see them move with such abrupt inhuman enthusiasm sickened my stomach and scorched an everlasting mark onto my amygdala. Yet, despite this experience, every time I’ve been to the beach since, I’ve tried to turn over a rock in the hopes of interrupting another crab gathering. Why do I do this with the foreknowledge that I’ll be horrified? And why am I disappointed when all I discover are seaweed and lugworm casts?

The crabs here are—as all crabs should be—metaphorical, the situation a microcosm of a larger human phenomena: engaging with horror fiction, turning pages instead of rocks. An ongoing example of this is the recent surge of popularity in pandemic related horror films on streaming websites during the Covid 19 crisis.[i] What is it about the nature of horror that compels some of us to its hideous maw? Why do we peep under rocks?

Curiosity is, arguably, the beating undead heart of horror. Noël Carroll demonstrates in The Philosophy of Horror[ii] that the very disgust and revulsion horror generates is key to why we are drawn to it.

Monsters…are repelling because they violate standing categories. But for the self-same reason, they are also compelling of our attention. They are attractive, in the sense that they elicit interest, and they are the cause of, for many, irresistible attention, again, just because they violate standing categories.[iii]

In my example, it’s not that I want to be horrified by crabs, it’s that the very curiosity that compels me to want to see them is contingent on that which makes me fear them: their exceptionality. This can be observed in ‘The Abduction Door’[iv]; the door violates ‘the mechanics of any universe [the protagonist] has been taught to believe in’[v], and therefore piques the audience’s interest and generates fear at the same time because it is an exception, an anomaly. Covid 19 is an example of a real-world monstrous exception, and therefore people are curious about it; they are engaging with pandemic media because they are fascinated and revolted by its exceptionality.

But why are human beings compelled to that which violates our conceptions of the known? Perhaps one of the more existential reasons that people engage with horror is due to our need to consolidate our identity and define what makes us human. In Limits of Horror: Technology, Bodies, Gothic[vi], Fred Botting reasons that ‘monstrous exceptions allow structures to be identified and instituted, difference providing the prior condition for identity to emerge. As exceptions to the norm, monsters make visible, in their transgression, the limit separating proper from improper, self from other.’[vii] In other words, the captivating pull of horror lies in its ability to present transgressions against the norm, and therefore make clear, in contrast, ‘what we are, what we are not [and] what we may be.’[viii]

Manuel Aguirre likens this process to an idea in Celtic mythology, in which the ‘wholeness of the world resides precisely in its link with the Otherworld.’[ix] He highlights this as the ‘paradox that a proper definition of a given thing in a given dimension requires reference to another dimension’[x]. For example, the paradise of heaven is arguably more compelling because of its stark contrast to the eternal damnation of hell. Paradise on its own could be considered meaningless, perhaps even pedestrian. Steven King agrees, stating that ‘we love and need the concept of monstrosity because it is a reaffirmation of the order we all crave as human beings’.[xi] In this view, ‘the monstrous are not strangers, after all, but the appalling potential of human evil.’[xii] Horror then presents the inhuman to bolster, by comparative distinction, our humanity.

If it is true, as modern physics attests, that ‘the observer is part of the thing observed’[xiii], then when we engage with horror fiction, we are seeing the light of ourselves burn bright in the darkness that the genre provides. And our fascination with the dark is enough make us turn over the rock.

[i] Alicia Adejobi, ‘Why are we watching pandemic movies like Contagion? Psychologist warns it could “amplify anxiety”’, Metro, 1 Apr 2020, Available at: https://metro.co.uk/2020/04/01/watching-pandemic-movies-like-contagion-psychologist-warns-amplify-anxiety-12493880/ [Accessed 5 Apr 2020]

[ii] Noël Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror (London: Routledge, 1990)

[iii] Ibid., 188.

[iv] Christopher Golden, ‘The Abduction Door’ in New Fears, ed. Mark Morris (London: Titan Books, 2017), 349-365.

[v] Ibid., 359

[vi] Fred Botting, Limits of Horror: Technology, Bodies, Gothic (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008)

[vii] Ibid., 8

[viii] Manuel Aguirre, The Closed Space: Horror, Literature and Western Symbolism (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990), 3.

[ix] Ibid., 4.

[x] Ibid., 10.

[xi] Steven King, Danse Macabre (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1981), 55.

[xii] Marina Warner, No Go the Bogeyman: Scaring, Lulling and Making Mock (London: Vintage, 1998), 261.

[xiii] Aquirre, The Closed Space, 10.